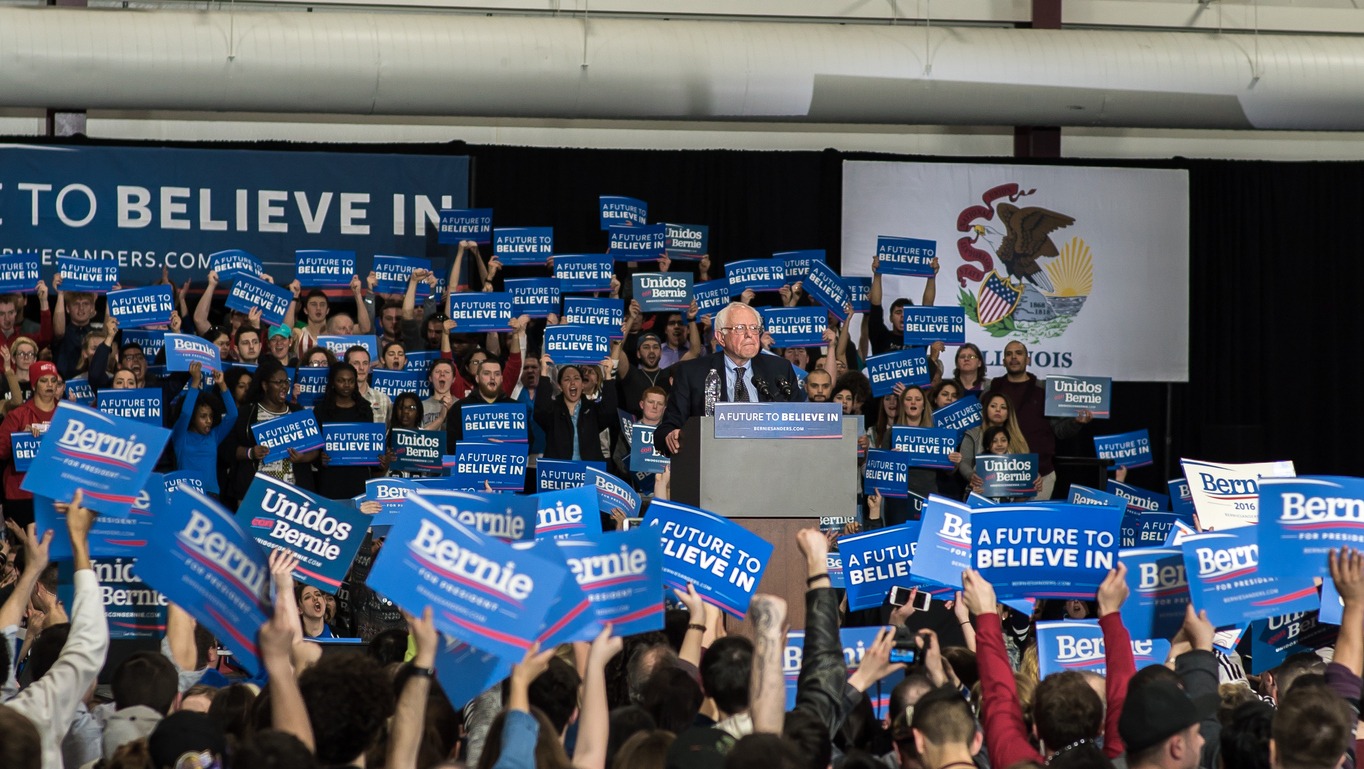

As economic inequality in the United States reaches historic highs, momentum is growing behind the idea of a wealth tax. Proposed by progressive lawmakers like Senator Elizabeth Warren and Senator Bernie Sanders, a wealth tax would directly target the assets of the ultra-rich, rather than their income. Supporters argue it’s a necessary step to rebalance an economy increasingly tilted in favor of capital, while critics warn it’s unworkable, economically risky, and potentially unconstitutional.

So, would a wealth tax work in the U.S.? History, international examples, and expert opinion paint a nuanced picture.

What Is a Wealth Tax?

A wealth tax is an annual levy on the value of personal assets—stocks, real estate, art, yachts, and other holdings. Senator Warren’s 2020 plan proposed a 2% tax on net worth above $50 million, and a 3% rate on wealth over $1 billion. Sanders’ plan was even steeper, reaching 8% for billionaires.

The Case For a Wealth Tax

1. Closing the Inequality Gap

America’s wealth gap has widened significantly. According to a 2022 report from the Federal Reserve, the top 1% of Americans now own more than one-third of all U.S. wealth. Meanwhile, the bottom half of the population owns just 2.6%.

“The rich are getting richer and the middle class is being hollowed out. A wealth tax is how we fix that,”

— Senator Elizabeth Warren, CNBC, 2020

2. Revenue Potential

Economists Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez, who designed Warren’s wealth tax proposal, estimate that her plan would generate $2.75 trillion over 10 years. They argue the IRS could enforce it with stronger reporting standards and digital auditing tools.

“The ultra-rich pay a lower effective tax rate than schoolteachers and firefighters. A wealth tax is about fairness.”

— Gabriel Zucman, Testimony before House Financial Services Committee, 2021

3. Global Precedents of Success

-

Norway taxes net wealth above $170,000 at a rate of about 0.85%, and has maintained relatively high equality with strong economic growth.

-

Switzerland has cantonal-level wealth taxes ranging from 0.1% to 1%, with little evidence of capital flight.

The Case Against a Wealth Tax

1. Administrative Complexity

Critics argue that accurately assessing and collecting a wealth tax is extremely difficult. Valuing assets like privately held businesses, art, or intellectual property each year requires immense bureaucratic capacity.

“Wealth taxes are inefficient and hard to enforce. They fail to raise much revenue and drive away capital.”

— Larry Summers, former U.S. Treasury Secretary, Brookings Institution, 2020

2. Evidence of Failure in Europe

-

France repealed its wealth tax in 2017 after losing an estimated 60,000 millionaires over a decade due to capital flight.

-

Sweden abandoned its wealth tax in 2007, citing low revenue and high administrative costs.

“We tried it. It didn’t work.”

— Emmanuel Macron, President of France, 2017, speaking about the wealth tax repeal.

3. Constitutional Questions

Some legal scholars argue that a federal wealth tax could violate Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, which restricts “direct taxes” unless apportioned by population—something wealth taxes aren’t.

“A wealth tax, as proposed, would immediately face constitutional challenge and likely be struck down.”

— Daniel Hemel, University of Chicago Law Professor, Tax Notes, 2019

The Wealth-Work Imbalance: Why a Wealth Tax Isn’t Just About the Rich

Critics and advocates alike agree on one thing: the current tax system disproportionately favors capital over labor.

-

Wages are taxed through income and payroll taxes, while wealth grows largely untaxed through unrealized capital gains.

-

In 2021, 55 of the largest U.S. corporations paid $0 in federal income taxes, despite reporting a combined $40.5 billion in pretax profits, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

-

Billionaires like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Warren Buffett pay lower effective tax rates than many working Americans, largely due to capital gains being taxed only upon realization.

“I pay a lower tax rate than my secretary. That’s just plain wrong.”

— Warren Buffett, speaking at the 2011 White House press briefing

“Taxing income while letting wealth compound untaxed is like bailing water with a hole in the bucket.”

— Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Laureate economist, 2023 panel at Columbia University

Rebalancing: Taxing Wealth, Not Just Work

There is a growing consensus among progressive economists that the tax code should shift its emphasis from income to wealth:

-

Implementing a mark-to-market tax on billionaires’ unrealized gains, as proposed by Senator Ron Wyden.

-

Closing loopholes like the “stepped-up basis” at death, which allows heirs to avoid capital gains taxes entirely.

-

Expanding IRS enforcement capabilities to pursue wealthy tax dodgers.

“The current system rewards those who inherit money more than those who earn it. That’s not capitalism—it’s aristocracy.”

— Senator Bernie Sanders, 2021 Senate Budget Committee hearing

Conclusion

A wealth tax in the U.S. could raise significant revenue and help close the growing inequality gap—if it’s thoughtfully designed and robustly enforced. But it faces steep legal, administrative, and political hurdles.

Ultimately, the debate goes beyond dollars and cents. It’s about fairness, the sustainability of democracy, and the kind of economy we want to build. Whether through a direct wealth tax or a broader restructuring of how capital is taxed, the time may be ripe for America to finally answer a question long deferred: Should the rich pay more—not just for what they earn, but for what they own?